Serious Question: Is the U.S. Spending Too Much?

Partisan sniping and congressional blame games belie a far greater divide.

Sign up to unveil the relationship between Wall Street and Washington.

Unless you have been hiding under a rock on the International Space Station, you know the U.S. reached a dangerous crossroads in recent days after hitting its debt ceiling of $31.4 trillion.

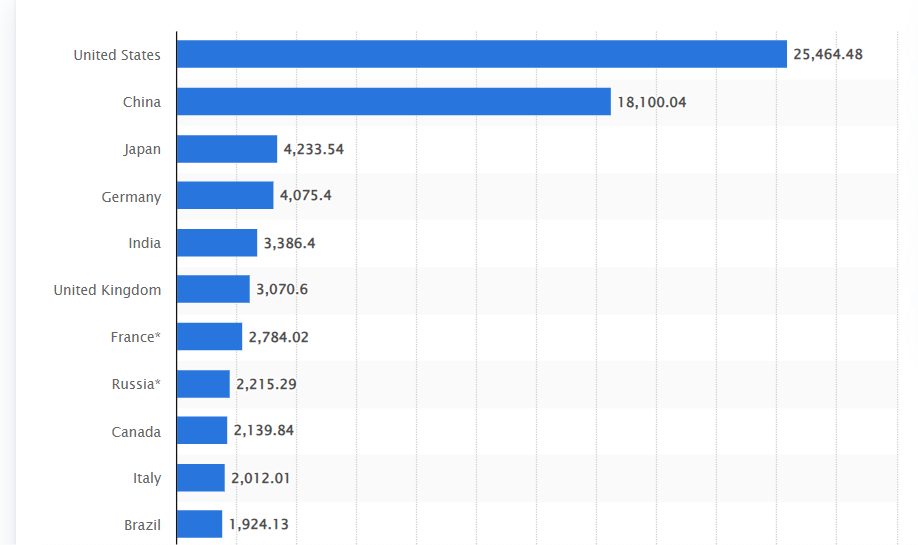

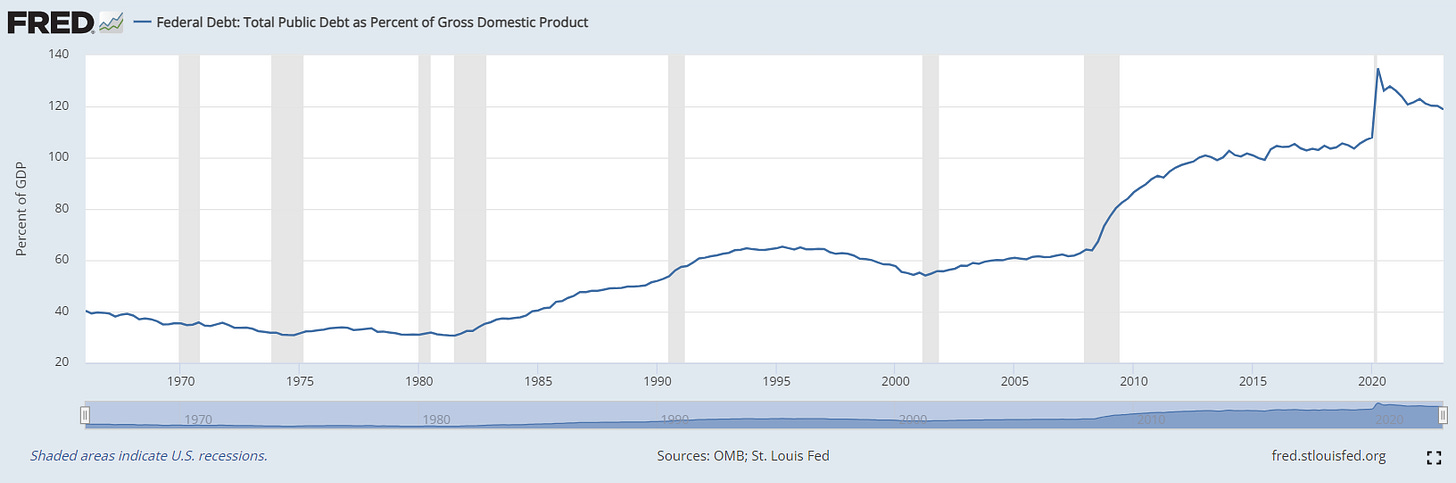

That’s approximately $6 trillion more than the nation’s annual gross domestic product (GDP), the total monetary value of all goods and services generated within America’s borders last year. In other words, the nation with the world’s largest GDP is spending far more than that annually (see chart, below).

This week, Congress faced a choice: either suspend the debt ceiling or raise it – or do neither and make it parlous, if not downright impossible, for the U.S. to borrow any more money, forcing it into default. As is well known, such an event would be ruinous for America’s economy, finances and global reputation.

As of this writing, a hard-won deal has been passed by the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate to suspend, but not raise, the nation’s debt ceiling through January 2025, in exchange for trimming government spending by $1.5 trillion over the next decade. Once President Biden signs it into law, which is expected to happen before the weekend, the U.S. will have at last averted skidding into a historic default.

Let’s think objectively for a moment about what these numbers tell us. House Republicans have been made into villains in some quarters (read: mostly by Democrats) for forcing this confrontation. But what’s the upshot? Some lawmakers effectively had to threaten to block the U.S. from borrowing any more money, pushing the nation to the brink of default, in order to shave a fractional $1.5 trillion from the budget over ten years.

This suggests that any reduction to U.S. spending of more than a trillion dollars is going to be exceedingly painful to do, even for a nation with the frothiest GDP on earth.

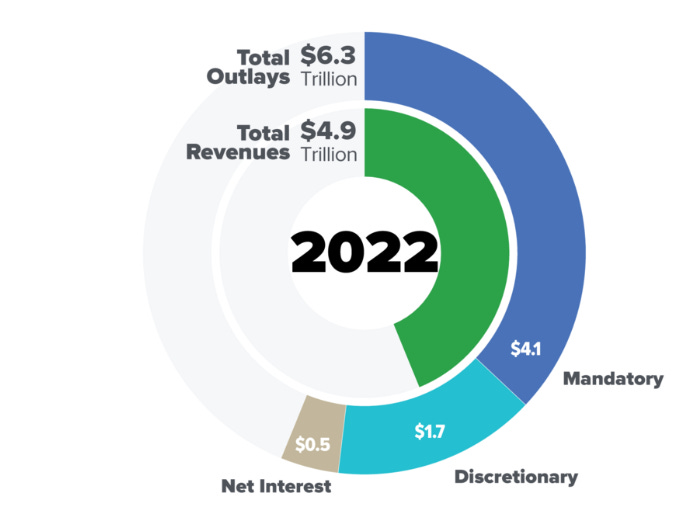

As a point of comparison, in just one year, 2022, the U.S. increased its deficit by nearly that much, $1.4 trillion, as its outlays exceeded revenue (see chart, below). So, the U.S. can burn through an extra one trillion-plus dollars a year quite easily, but needs at least a decade, best-case scenario, to save or reduce its costs by the same amount.

This is cause for both parties, Democrat and Republican, to weigh a course correction. “Both sides are concerned about high deficits and ballooning debt,” says David Andolfatto, professor of economics at the University of Miami and former senior vice president at the St. Louis Fed. “But how to do it?”

With all the political theater of the past several weeks, it’s reasonable to wonder who is telling the truth about American spending — and if there’s any room to spend less, or at least generate more revenue, so the country is not so reliant on borrowing endlessly just to keep the lights on.

Even for those who would like to see America spending more on education, military, energy, healthcare, science, social programs or the like, these data plainly illustrate why the country might benefit from taking a completely surgical look at how it is raising and spending its money. (This is discussed in additional detail in an earlier issue of Power Corridor here.)

“This fight over the debt ceiling, crudely, is a clash between those who want a larger — or smaller — government footprint in the lives of Americans,” Andolfatto tells Power Corridor. “On the Democratic side, there’s the notion we need to spend more on infrastructure, schools, water supplies, internet access and social programs. And they think the way to finance this is by raising taxes. On the GOP side, we have the opposite view. They think we have too much discretionary spending, too many programs and we don’t need to raise taxes, but to cut spending.”

Even with America dodging catastrophe next week, what about its trajectory over the long haul? Turning away from the partisan pearl-clutching, some of the world’s most prominent credit ratings agencies have voiced their alarm. Late last week, one of them, Fitch, put the nation’s top-notch ‘AAA’ credit rating on negative watch, citing a series of problems. “The brinkmanship over the debt ceiling, failure of the U.S. authorities to meaningfully tackle medium-term fiscal challenges that will lead to rising budget deficits and a growing debt burden signal downside risks to U.S. creditworthiness,” it wrote, noting the U.S. Treasury’s cash balance had dropped to $76.5 billion as of May 23.

In 2011, just days after Washington narrowly sidestepped another default due to political infighting, credit ratings agency S&P downgraded U.S. sovereign debt from ‘AAA’ to ‘AA-plus.’ John Chambers, who oversaw that downgrade as former chairman of the S&P Sovereign Rating Committee, said this week that, in light of recent events, he stood by the decision. “This validates S&P’s decision in 2011 to lower the rating,” he told CNBC. “It’s simply not consistent to have an ‘AAA’ rating and the prospect [the U.S. could] run out of cash and not pay its debt.”

Chambers laid out a longer-term case. “You have two major problems,” he said. “One is the fractiousness of the political environment. The fact we had a coup d’état, a failed coup d’état, two years ago [Jan. 6, 2021] certainly would be an indication of that.

“And the second is the debt trajectory. Even with this deal…the debt burden, the amount of government debt as a share of economic output, is going to continue to rise and, although that in itself is not a problem, now you need a medium term fiscal correction. Because otherwise you’re going to use up your ammunition when you do enter into a recession, or we have some major problem to face, like a war or something like that. You want to have some dry powder ready for eventualities.”

Speaking of, what is the share of government debt versus economic output? I am not going to overwhelm you with any more charts and numbers, tender reader. Except for this one: As a percentage of annual GDP, government debt has now spiked well above 100 percent over the course of the past decade. In some cases, it has even leapt to nearly 140 percent (see chart, below, with shaded areas denoting when the U.S. was in recession).

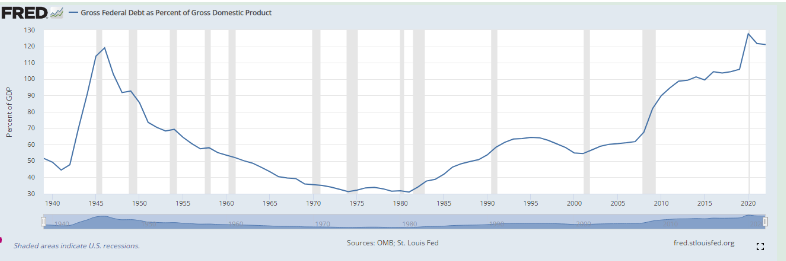

At its peak these past few years, the federal debt-to-GDP ratio has been unmatched, but during World War II it spiked to nearly 120 percent. The U.S. managed to pull itself out of the hole by the 1980s, as can be seen by the chart below, but it took nearly four decades, which should be sobering.

Technically, the U.S. has the power to print money and raise funds by issuing more debt, continuously rolling it over for future payment and raising the debt ceiling to increase the amount it might borrow through the authorization of Congress and the President.

But these things come at a cost, Andolfatto says, because a rising money supply sloshing through the system can cause inflation.

In fact, inflation and the rising cost of living is a major factor hurting Americans right now. Until inflation cools off, increased government spending can potentially make the situation worse. “If the question is, can the deficit be too big, the answer is yes, if it is causing inflation,” he says.

Chambers added that the amount of debt a nation has, regardless of inflation, can also pose problems. “Your capacity to pay debt is, in part, a function of how much debt you have outstanding,” he said. “The more debt you have outstanding, the more difficulty you might have rolling it over, the more difficulty you might have in servicing it. That’s what the credit rating speaks to, and it’s not the only factor that goes into a rating, but it’s an important factor.”

Even if the U.S. theoretically eliminated all its debt, stopped borrowing and only spent what it raised in tax revenue, that likely still wouldn’t prevent it from overspending, Andolfatto notes.

“The question of whether we’re spending too much – what do we mean by that?” he asks. There is still such a thing as spending too much, even when you have the money, or spending unwisely, or making a bad investment, or just being wasteful.

“Overspending means different things to different people,” he says. “That’s why this is such a complex issue.”

Take another thought experiment: What if the spending in question is agreed upon by all, expertly budgeted and justified? (Not that this would ever happen, but for the sake of the argument.) Is there a limit to how much should be spent?

The answer, as you might have guessed, is yes. But again, it depends. “If you continue to spend, spend, spend and you are not raising taxes to cover it, eventually it will result in inflation,” Andolfatto says.

“If taxes don’t cover spending, that means the government is going to be deficit-financing things. And if you don’t keep taxes in line with spending, you can set yourself up for inflation.”

Hmmm. Spending only what is raised in tax revenue? What a novel idea.

Power Reads:

A selection of recent reads, for your weekend cogitation.

In a nation where some of the wealthiest have made a parlor game of dodging their taxes, here is the story of one man, a Marine Corps veteran, who owed $134 in property taxes. He was torn from his home by armed U.S. marshals and tossed to the curb like garbage, so an investor who purchased his lien could profit. Undertaking a 10-month investigation, The Washington Post’s Michael Sallah, Debra Cenziper and Steven Rich examine how thousands of vulnerable homeowners have been preyed upon with impunity by vultures — and what is being done about it. This article also has some of the most heartbreaking photos, by Michael Williamson, I have ever seen. A story very much worth reading.

When Americans pulled out of Afghanistan in 2021 and the Taliban marched into Kabul, many of the Afghans who worked alongside Americans for two decades to bring democracy to the country found themselves completely abandoned and forced to flee, lest they be hunted and killed. Julie Turkewitz of The New York Times details how thousands of Afghans “trudged through the jungle, slept on the forest floor amid fire ants and snakes, hid their money in their food to fool thieves and crossed the sliver of land connecting North and South America,” just to get to the American border. But what happens next? A stunningly told long read, filled with photos and video by Frederico Rios.

Now for something more summery and uplifting. Masha Udensiva-Brenner penned a shimmering essay for The Delacorte Review on the only natural forest in Manhattan, Inwood Hill Park. “Most New Yorkers haven’t even heard about Inwood,” she writes. “If you’re out in the neighborhood enough, you end up recognizing not just the people but their dogs too…Inwood Hill Park was the neighborhood’s best feature. It was filled with rocks and hills and winding trails. We walked there almost every day, thinking of it as ours because we were almost always alone.” She also tells the story of a the park’s “mystical” teepee, “a tall, triangular structure with a round base that sat on a clearing in the valley of the forest” and her quest to understand its origins and why it seemed to repeatedly disappear and reappear.

That’s it for this week — thank you for reading, as always, and have yourselves a great weekend !